Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental health conditions, affecting individuals across the lifespan. While they are often recognized in adulthood, research underscores their roots in childhood, with many anxiety disorders manifesting during the pediatric years. Despite their prevalence, these disorders remain underdiagnosed and undertreated, which can lead to lifelong challenges if left unaddressed.

Prevalence and Onset of Pediatric Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders affect approximately 34% of the adult population during their lifetime, with symptoms typically beginning in childhood. The median age of onset for anxiety disorders is six, significantly earlier than depressive disorders, which have a median onset age of thirteen. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), identifies several specific anxiety disorders relevant to pediatric populations: generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and specific phobia.

The types of anxiety disorders children experience often correlate with developmental stages:

- Specific Phobia: Emerges around six years of age.

- Separation Anxiety Disorder: Onset is typically around eight years.

- Social Anxiety Disorder: Commonly appears by age twelve.

- Generalized Anxiety and Panic Disorders: Tend to develop after puberty.

The prevalence of anxiety disorders increases with age, with females consistently showing higher rates of diagnosis across all developmental stages. Among post-pubertal youth, social anxiety disorder is the most common, affecting approximately 9% of the population. Early recognition and intervention are critical to preventing the progression of these disorders and mitigating their long-term impact on social, academic, and emotional functioning.

Risk Factors Contributing to Pediatric Anxiety

The development of pediatric anxiety disorders is influenced by a complex interplay of genetic, biological, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Key contributors include:

- Genetic and Biological Influences:

- A strong genetic link exists for children whose parents have anxiety disorders.

- Structural and functional alterations in the brain’s frontal limbic regions are associated with anxiety.

- Parenting Styles and Family Dynamics:

- Parental stress, maternal depressive symptoms, and overprotective parenting are strongly correlated with childhood anxiety.

- Poor attachment in early childhood exacerbates vulnerability to anxiety disorders.

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs):

- Children exposed to abuse, domestic violence, or parental substance use are at heightened risk for anxiety.

- Other ACEs, such as parental divorce, discrimination, and foster care placement, further increase susceptibility.

- Environmental and School-Related Stressors:

- Bullying, social isolation, academic pressure, and high expectations from teachers contribute significantly to pediatric anxiety.

- High-achieving and perfectionist children are particularly vulnerable due to their fear of failure.

- Lifestyle Factors:

- A sedentary lifestyle, characterized by limited physical activity, is linked to cognitive impairments, low self-esteem, and increased anxiety.

- Chronic health conditions resulting from inactivity, such as obesity, exacerbate mental health challenges.

- Co-Morbid Conditions:

- Anxiety often coexists with depression, ADHD, and emotional dysregulation, compounding diagnostic and treatment complexities.

Understanding these multifactorial contributors is essential for clinicians aiming to design effective diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Diagnostic Strategies for Pediatric Anxiety Disorders

Early and accurate diagnosis of pediatric anxiety disorders is crucial to ensure timely interventions. The review emphasizes several diagnostic approaches, including active listening, structured clinical assessments, the use of screening tools, and comprehensive differential diagnosis.

- Active Listening:

- Active listening enables clinicians to build trust with patients and families, uncover subtle signs of anxiety, and establish rapport.

- By attentively observing a child’s verbal and non-verbal cues, clinicians can detect symptoms like fear of separation or avoidance of social interactions.

- Clinical Assessments:

- A structured interview process ensures consistency and reliability in diagnosing anxiety disorders.

- Assessments should include the patient’s chief complaint, medical and psychiatric history, developmental milestones, and a mental status examination (MSE).

- Physical symptoms, such as recurrent gastrointestinal distress, and behavioral signs, like withdrawal from peers, can indicate anxiety.

- Screening Tools:

- Standardized tools, such as the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17), support clinicians in identifying anxiety symptoms and tracking treatment progress.

- Integrating these tools into electronic health records (EHRs) streamlines documentation and facilitates referrals to mental health specialists.

- Differential Diagnosis:

- Clinicians must differentiate anxiety disorders from conditions like ADHD, depression, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and learning disabilities.

- Medical conditions, including thyroid dysfunction and migraines, should be ruled out through appropriate diagnostic testing.

The Role of Primary Care in Early Detection

Primary care settings play a pivotal role in identifying and addressing pediatric anxiety disorders. Routine mental health screenings are strongly recommended by organizations such as the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Key findings include:

- Parents overwhelmingly support routine mental health screenings for their children, citing benefits like early problem detection, access to resources, and symptom management.

- Tools such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) and Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17) are effective for identifying internalizing disorders like anxiety and depression.

- Incorporating screenings into annual wellness visits promotes early detection and intervention, improving long-term outcomes.

While implementing universal screening protocols requires an initial investment of time and resources, the benefits far outweigh the challenges, enhancing both patient outcomes and care efficiency.

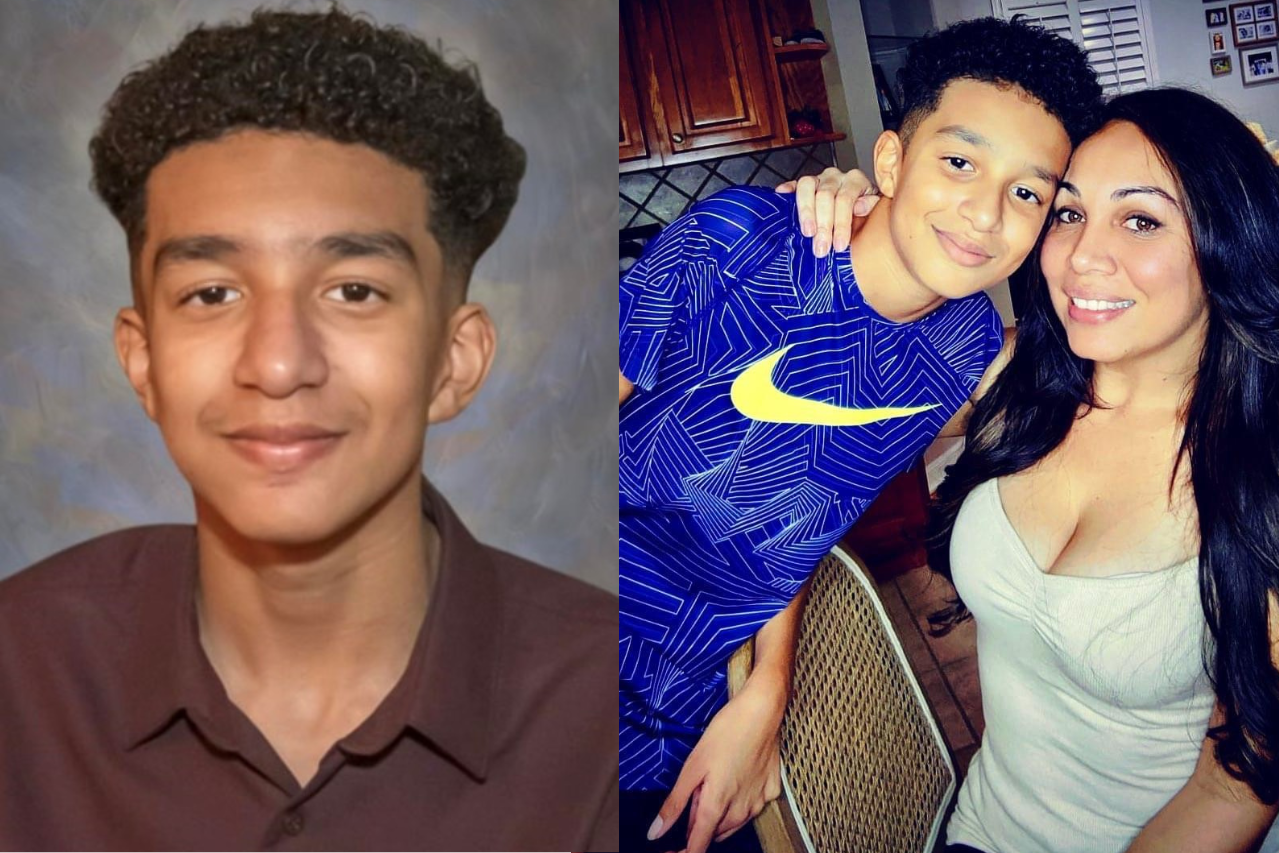

Risk Assessment for Suicide and Self-Injurious Behaviors

Anxiety disorders, particularly when accompanied by depression, significantly increase the risk of suicidal ideation and attempts. Risk assessment tools, such as the SAFE-T protocol and the Brief Suicide Safety Assessment (BSSA), help clinicians evaluate the severity of suicidal behaviors and formulate appropriate safety plans. These assessments should be conducted in a private, supportive environment to encourage honest disclosure.

The Emerging Role of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Anxiety Care

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers promising applications in the diagnosis and management of pediatric anxiety disorders. While AI cannot replace clinicians, it can enhance care delivery in the following ways:

- Supportive Tools:

- AI-powered chatbots and robots can help reduce anxiety during medical procedures or therapy sessions.

- Predictive modeling aids in identifying risk factors and refining diagnostic accuracy.

- Gamification and Adherence:

- AI-based games and reminders improve treatment adherence in young patients.

- However, clinicians must monitor AI interventions to avoid unintended adverse effects, such as exacerbating anxiety.

The integration of AI into pediatric mental health care remains in its infancy, requiring further research to establish evidence-based guidelines and ethical safeguards.

Evidence-Based Recommendations for Clinicians

To optimize care for pediatric patients with anxiety disorders, clinicians should:

- Begin routine anxiety screenings by age 8 (USPSTF) or age 11 (AAP).

- Use validated, age-appropriate, and culturally sensitive screening tools.

- Collaborate with families, educators, and mental health specialists to develop comprehensive treatment plans.

- Stay informed about emerging research and innovations in AI-supported diagnostics and interventions.

Future Directions in Pediatric Anxiety Research

The review highlights the need for further research to address gaps in pediatric anxiety care:

- Cultural Sensitivity:

- Develop screening tools that account for gender, ethnicity, and cultural variations in anxiety presentation.

- Global Applications:

- Use AI to analyze international mental health data and identify trends in pediatric anxiety disorders.

- Integrated Care Models:

- Foster partnerships between primary care providers and mental health specialists to streamline referrals and interventions.

Anxiety disorders in pediatric populations are a significant public health concern. Left untreated, they can lead to lifelong challenges, including impaired academic performance, social isolation, and increased risk of mood and substance use disorders. Routine screenings, early interventions, and a collaborative care approach are essential to improving outcomes for affected children and adolescents. While AI holds great promise as a supplementary tool in pediatric mental health care, its use must be guided by ethical considerations and evidence-based practices.

Click here to learn more about pediatric anxiety disorders, their diagnosis, and innovative treatment approaches.